A constitution for matter that demonstrates evaporation

Our picture demonstrates 'evaporation' from a black hole. Matter may be re-encoded into forms that may escape, and we interpret the classical Schwarzschild radius as a statistical quantum zone that is conventionally considered to be the point of no return for inwardly-falling matter.

What is a black hole?

Generally, a black hole is a region where gravitation (or, in terms of General Relativity, space-time curvature) overcomes any other forces that would otherwise allow matter to escape. The early common interpretation was that nothing can escape; speculation in quantum mechanics suggests that some matter escapes every black hole, and that a black hole eventually 'evaporates' via radiation.

The Re-encoding of matter

In the constitution article, we describe how conserved fermions may re-constitute from bosons. This structure for matter allows the constituent parts of a fermion to collapse independently as fermionic couplings with external bosons or vacuum energy.

|

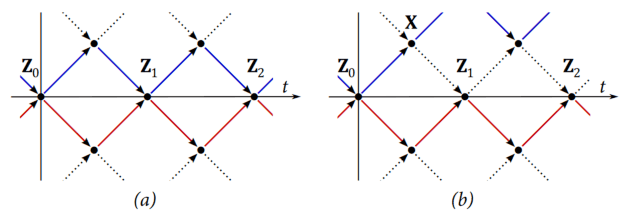

| Fig.1: (a) Persistent state, and (b) a change of constitution. |

These vacuum-coupled fermions may then in turn re-radiate the same bosons, which collapse back to the original fermion (fig.1a: Z1). If that fails to happen, then the two parts of the fermion will go their separate ways (fig.1b), losing coherence, with the probability of re-constitution becoming less likely in the process; they might never reconstitute the original fermion again.

The (probabilistic) point of no return

Rather than simply assuming a classical radius for the threshold of a black hole (the Schwarzschild radius), our physical model implies that the direction (that a boson resolves itself to) is dependent on near-local vacuum conditions (other bosons that are passing as fields, or are in the required phase to help constitute fermion events).

It is therefore a probabilistic boundary, the condition for escaping radiation being that the vacuum in the locality contains bosons having low mass-energy, so that a fermion state (though not necessarily the same constitution or matter type) can have a 'good run' in the outward direction. Conditions would be more favourable in the presence of dipoles, which may provide outward solutions assisted by electromagnetic fields or vacuum currents, so we would expect radiation to be at localities having high charge.

Quantum escape

We use this process as basis for the proposition that matter may re-encode itself to forms that may radiate past the Schwarzschild boundary.

In our mass-energy article, we show how massive bosons are less likely to propagate far before they collapse, and conversely, light bosons may propagate great distances before being collapsed. With this in mind,

Hawking radiation

Rather than Hawking radiation being a special case for the event horizon, we exploit the same mechanism that we use to formulate the conservation of a fermion, using the case where the fermion fails to reconstitute.

One commonly-hypothesised mechanism for Hawking radiation describes particle/anti-particle pairs that are spontaneously created from vacuum but fail to correspondingly annihilate, instead becoming separated. This differs from our picture, only because we model conserved fermions as regularly splitting into virtual components to interact with vacuum; the quantum outcome is similar.

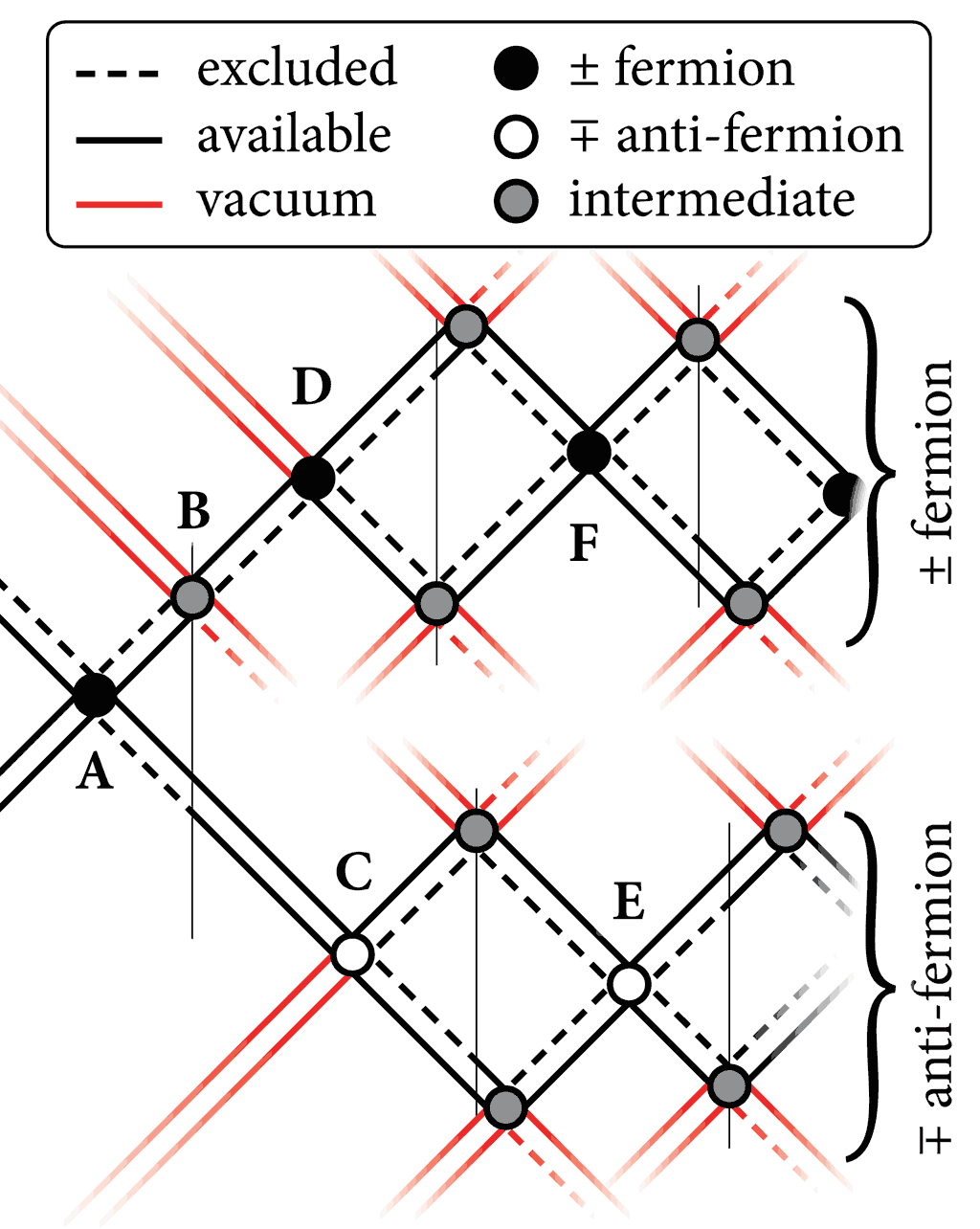

Taking this higher up the emergence scale, this manifests as either radiation, where the outer constituent bosons do not collapse, or more likely in dense environments, reconstitution is interrupted, and the bosons reconstitute separately, perhaps with longer-lasting conserved products, fig.2, below.

For all of these, it is more likely that the more massive constituents are retained closer to the body, and the 'lighter' bosons are radiated away. How far depends on the density and coherence of the vacuum.

Fig.2: Hawking radiation is not a special case.[15]

Avoid mass

Where the mass-energy of the body is significant, a boson's spherical wave will need to avoid crossing the body, for an increased probability of escape.

If a boson's waves generate new fermion events on their escape path, then the radiated boson originates from a point further from the central mass, and can more easily reach a safe distance where they may be considered to be 'radiation' from the main body.

Can this help to solve the black hole information paradox?

The black hole information paradox is founded on the idea that a black hole seems to destroy information. Using the above, and treating the information as individual waves or bosons, rather than as fermions or composite particles, we find that although the matter may change constitution within the body, and separate to generate radiation, the overall mass-energy will be conserved, and nothing is destroyed.

Entering the black hole

Any regular matter entering a black hole is likely to be absorbed into the main body. On its way in, the matter will be unable to maintain its constitution, as the dense flux contributes a greater probability of collapse to the matter, intercepting the usual re-constitution process. Lighter parts will be stripped away first, like electrons, and any bosons that were tenuously confined. As the environmental flux increases, the matter will be increasingly challenged, and eventually overcome, its bosons contributing to the plasma of the environment and eventually to the body of the black hole itself.

Inside the black hole

When inside the black hole, the original matter will be unrecognisable. The largest conserved units will be the bosons, which will have been separated from their 'siblings', with improbable chance of ever re-constituting in the form they entered. Any higher-level structures will have been destroyed, their bosonic parts scattered. The fermions that those bosons do make will have new identities, using parts that will likely have never met before. The environment will be an intense plasma, with bosons interacting at a rate many orders of magnitude higher than in the human environment, or even within a star.

Inside the black hole is a plasma of bosons, forming temporary fermions whose ideneities are unlikely to ever be repeated (having unique constituents every time). Lighter bosons will conduct through structures of massive bosons, with the massive bosons migrating towards the centre of the structure because that's where the directional probability of collapse will take them, as per our definition of gravitation.

Distillation

Given that the heavier bosons are drawn inwards, and therefore the lighter bosons are not, there is a tendency for the matter to be distributed radially by their mass-energy. Further, the lighter bosons have a higher probability of evaporation, which is when the environmental flux outside the black hole is capable of successively collapsing a boson outwards, against the probabilities implied by the flux gradient.

This is analogous to distillation, where lighter fractions more readily evaporate than heavier fractions.

Outer accretion shell

Given a black hole of sufficient size, containing a significant number of massive bosons, it will be composed of a significant amount of confining matter. Near its surface, massive bosons collapse the radiation before it can escape, which creates a vacuum flux that is weaker than the surrounding environment. It might seem surprising that a visiting body can be so close to a massive body like a black hole, and yet not be subjected to any gravitational force from it. Further, because there is a denser vacuum flux outside the vicinity of the black hole, the flux gradient attracts matter away from the surface.

Our resulting predictions: for such black holes, there is a 'shell' zone of equilibrium, some distance from the surface of the black hole, where matter may accumulate. This is fed by the inward accretion of vacuum flux, which may also carry matter inwards from the surrounding space.

With enough accumulated matter in the shell, that shell might also become confining. Further, many strata of such shells may form. Although these layers are confining, they may be self-regulating, due to their shielding of vacuum flux.

The late universe

After a black hole is firmly established, it will accumulate matter until the environment can no longer provide it. After that, there will be a point in time where it will radiate more mass as lighter bosons than it absorbs in ordinary matter, while confining the massive bosons. This evaporation will occur in notably longer evaporation stages with each tier of mass, each stage being several orders of magnitude longer than the previous, simply because the overall probabilities of escape are a function of a very high power to the quantum probability of escape.

We predict that the late universe will contain only light bosonic radiation, and black holes having a high-mass confined flux, like a giant exotic hadron. Predicting the flux density of environmental low-mass radiation, such as neutrino constituents, depends on cosmological expansion being included or omitted.

Summary

Throughout our description of a black hole, we have used no special mechanisms that are unique to a black hole; only a mechanism that is common to all matter.

The most notable feature is that our description of gravitation, as an emergent statistic of the collapse of fermions, serves the model well here, providing the internal stratification of the black hole, its flux gradients, and its evaporation characteristics. Further, we have explained Hawking radiation, along with a deterministic basis for quantum fluctuations, again without specific mechanisms.

Bridge incompatible representations

We are hopeful that this mechanism might help with understanding a possible framing for the quantization of gravitation, while not explicity combining General Relativity and Quantum Mechanics. Where leading theories are treating gravitation as an addition to the quantum properties (or vice versa), we count them once, as the same interaction. You can read more about this in Quantization of Gravitation.

- I describe black holes briefly in the final chapter of An Absolute Phase Space for the Physicality of Matter [12], and more thoroughly in my 2014 Black Holes paper.